When was the last time you noticed behaviour that felt unpleasant and paused to ask yourself, what might this person be going through?

Most people will experience trauma at some point in their lives, or witness something that leaves a lasting impact. In the UK, around one in three adults will go through a traumatic event such as serious injury, abuse, or significant loss. Trauma is also common in childhood, with over 30% of young people affected, and around one in 13 developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) before the age of 18.

Trauma does not look the same for everyone, and its effects can vary widely depending on the experience, timing, and support available. Understanding the different types of trauma helps make sense of these responses and highlights why care and support must always be shaped around each person’s lived experience.

Trauma is widely recognised as a leading underlying contributor to mental health difficulties, particularly when exposure is prolonged, repeated, or occurs during early childhood.

What Is Trauma?

Trauma may follow a single event, such as an accident or loss, or develop through repeated experiences like neglect, abuse, or prolonged stress.

When trauma becomes more than a person can cope with, even ordinary daily tasks can feel difficult. People may experience intrusive memories or flashbacks, heightened anxiety, low mood, sleep disturbance, or difficulties trusting others. Research consistently shows that trauma also affects the body, not just emotions.

Many people report ongoing fatigue, headaches, gastrointestinal problems, or chronic pain, reflecting how stress responses can remain active long after danger has passed. Cognitive changes are common too, with difficulties around concentration, memory, and decision-making, particularly during periods of stress.

Although some people go on to develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), many do not meet diagnostic thresholds yet still live with the long-term effects of trauma. These responses are not signs of weakness or pathology; they are understandable survival adaptations shaped by past experiences.

Recognising trauma in this way helps shift the focus from “what is wrong?” to “what has happened?”-creating space for understanding, safety, and recovery.

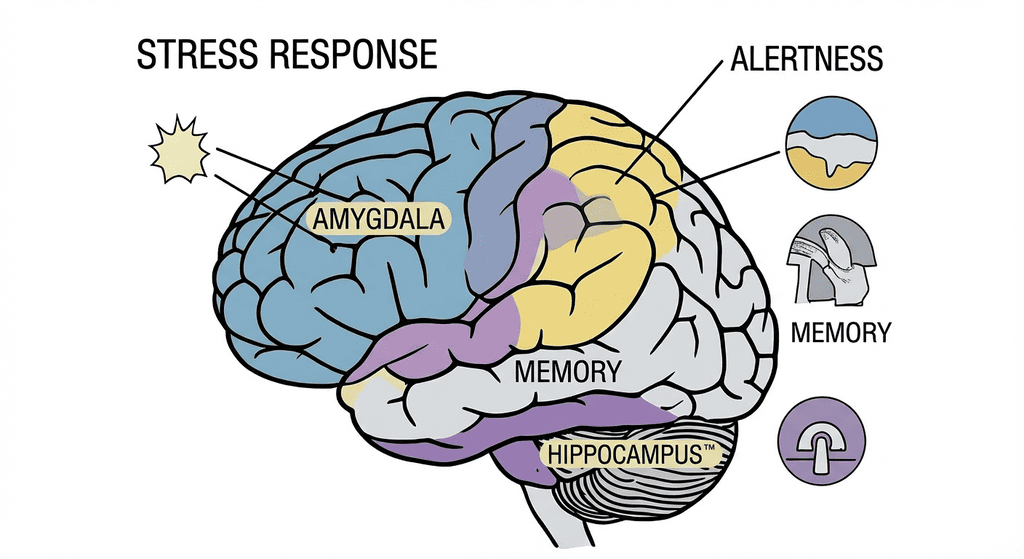

The Brain’s Response to Trauma

When a traumatic event happens, the brain’s first priority is survival. It reacts faster than conscious thought, scanning for danger and shifting the body into protection mode. Stress hormones surge, heart rate increases, and parts of the brain responsible for reasoning and emotional balance step back. This response can be lifesaving in the moment, but when trauma is ongoing or unresolved, the brain may stay on high alert, even when life becomes safer.

This is where the fight, flight, freeze, or fawn responses come in. Fight pushes the body to defend itself, flight urges escape, freeze shuts things down when no option feels safe, and fawn leads to people-pleasing as a way to avoid harm. These reactions are not flaws or conscious decisions – they are the brain doing its best to protect life. When they persist over time, they can shape emotions, behaviour, and relationships, often leaving people feeling stuck in survival rather than able to live fully.

What Does Traumatised Mean?

Being traumatised can show up in everyday life in many different ways. For example, someone who has experienced violence or abuse may feel constantly alert, startle easily, or struggle to relax, even in safe environments. Others may emotionally shut down, finding it hard to feel joy, connection, or trust, because their nervous system has learned that closeness can feel unsafe.

Trauma can also affect behaviour and relationships. A person who has lived through neglect or repeated rejection might avoid asking for help, become overly independent, or feel intense fear of abandonment. Another may respond by pleasing others, agreeing to things they are uncomfortable with, or suppressing their own needs to avoid conflict. These patterns are learned survival responses shaped by past experiences.

The Three Main Types of Trauma

Trauma can take many forms, and understanding these differences helps explain why people respond in such varied ways. While every experience is personal, trauma is often grouped into three main types to help make sense of how distressing events affect the mind and body over time.

Acute Trauma

Acute trauma occurs after a single, sudden, and distressing event that overwhelms a person’s ability to cope in that moment. This may include experiences such as a serious accident, physical or sexual assault, a medical emergency, natural disaster, or witnessing violence. Research shows that most people will experience at least one potentially traumatic event in their lifetime, and for many, the immediate aftermath brings intense emotional and physical reactions as the nervous system remains on high alert.

In the days and weeks following an acute traumatic event, people may experience a range of responses, including:

- Intrusive memories or flashbacks, where the event feels as though it is happening again

- Heightened anxiety, fear, or panic, especially when reminded of what happened

- Sleep disturbance, nightmares, or difficulty relaxing

- Emotional changes, such as shock, sadness, anger, guilt, or emotional numbness

- Physical symptoms, including headaches, fatigue, nausea, or muscle tension

These reactions are common and reflect the body’s attempt to protect itself in response to perceived danger.

For many people, symptoms gradually ease as safety is restored and support is available. However, evidence suggests that around 1 in 4 people exposed to acute trauma may continue to experience significant distress beyond the initial recovery period.

Without understanding and support, acute trauma can develop into longer-term difficulties. Recognising acute trauma early helps people recover more effectively and rebuild a fulfilling life.sing acute trauma early helps people recover more effectively and rebuild a fulfilling life.

Chronic Trauma

Chronic trauma develops through prolonged or repeated exposure to distressing experiences, particularly when there is little opportunity for safety, escape, or recovery. This may include ongoing abuse, neglect, domestic violence, bullying, exploitation, repeated discrimination, or long-term exposure to fear and instability. Unlike single-event trauma, chronic trauma keeps the body and mind in a near-constant state of threat. Studies show that repeated traumatic exposure significantly increases the likelihood of long-term mental and physical health difficulties, especially when experiences begin in childhood.

Over time, living under sustained stress can reshape how a person understands safety, trust, and relationships. Common experiences include:

- Persistent hypervigilance, always anticipating danger

- Emotional dysregulation, with intense emotions or emotional shutdown

- Difficulties with trust and attachment, particularly in close relationships

- Changes in thinking, such as low self-worth, shame, or a sense of helplessness

- Ongoing physical symptoms, including chronic pain, fatigue, headaches, or gastrointestinal issues

These responses reflect survival in environments where threat was ongoing rather than temporary.

Complex Trauma

Complex trauma develops when a person lives through ongoing harm or instability over time, often in situations where safety, care, or protection should have been present but were not. It is closely connected to chronic trauma, but goes deeper because it is usually relational – involving caregivers, family members, authority figures, or systems meant to offer support. This can include long-term abuse or neglect, repeated placement moves, domestic violence, or growing up in environments shaped by fear, unpredictability, or emotional absence.

Because this kind of trauma is lived with rather than survived once, it shapes how a person learns to exist in the world. People may struggle to feel safe even when no immediate danger is present. Trust can feel risky. Emotions may swing between feeling too much and feeling nothing at all. Some people describe a constant sense of shame, self-blame, or confusion about who they are, while others feel disconnected from memories, their bodies, or relationships. These are not choices or flaws – they are ways the mind and body learned to survive for a long time.

The impact of chronic and complex trauma often continues into adulthood, not because people are “stuck,” but because their nervous systems learned that danger was normal. Healing usually takes time and consistency. What helps is not quick fixes or pressure to move on, but experiences that slowly rebuild safety, trust, and connection. Understanding complex trauma in this way allows care and support to respond with patience, compassion, and respect for how hard survival once was.

Types of Trauma Based on Experiences

Trauma comes from experiences that feel frightening, overwhelming, or unsafe, and that stay with a person long after the moment has passed. These experiences can happen once, build up over time, or occur within relationships and environments where protection should have existed. Grouping trauma by experience helps explain how different life events leave different kinds of emotional and physical traces.

Physical Trauma

Physical trauma can arise from physical abuse or serious physical injury, especially when pain, fear, or lack of control are involved. It may follow experiences such as being hit, restrained, or harmed by another person, as well as accidents, assaults, or medical events that place the body under extreme stress. These experiences can leave a lasting sense of vulnerability, even after visible injuries have healed.

People living with physical trauma often describe feeling on edge in their bodies, startled by sudden movement, touch, or noise. Pain, tension, or fear may return through memories held in the body rather than in words. For some, trust becomes difficult, particularly around those who are physically close. These responses are not overreactions; they reflect the body remembering what it took to stay safe when harm once occurred.

Emotional or Psychological Trauma

Emotional or psychological trauma develops through emotional abuse, repeated criticism, humiliation, rejection, or being made to feel unsafe, worthless, or unseen over time. These experiences often happen within close relationships, which can make them difficult to recognise and even harder to talk about. Words, tone, silence, and control can wound deeply, shaping how a person understands themselves and the world around them.

Examples of experiences that can lead to emotional or psychological trauma include:

- Being constantly criticised, shouted at, or belittled

- Being ignored, dismissed, or emotionally withdrawn from as punishment

- Being told repeatedly that feelings are wrong, dramatic, or imagined

- Living with threats, intimidation, or controlling behaviour

- Being blamed for things outside one’s control

- Growing up without reassurance, comfort, or emotional safety

- Being manipulated through guilt, fear, or shame

- Feeling pressure to meet unrealistic expectations to avoid conflict

People affected by emotional trauma often carry self-doubt, fear of making mistakes, or a strong need to please others. Expressing needs may feel unsafe, and trusting emotions can be difficult. Even without visible scars, emotional abuse can leave lasting effects on confidence, relationships, and a sense of safety.

Developmental Trauma

Developmental trauma occurs when a child grows up in environments where safety, consistency, or emotional care are missing, particularly during early years when the brain and nervous system are still forming. This may involve ongoing neglect, emotional or physical abuse, exposure to violence, frequent moves, or caregivers who are unavailable, unpredictable, or overwhelmed. When stress is constant during development, the child’s body learns to stay alert for danger, even when no immediate threat is present.

Trauma during development often shows up in everyday life rather than as a single memory. Common trauma-related experiences include:

- Difficulty managing emotions, with sudden outbursts or emotional shutdown

- Problems with attention, concentration, or learning

- Strong reactions to change, touch, or perceived criticism

- Sleep difficulties, nightmares, or ongoing tiredness

- Challenges with trust and relationships, including fear of closeness or rejection

- Low self-esteem, shame, or feeling “different” from others

- Physical complaints, such as headaches, stomach pain, or frequent illness

These responses reflect adaptation to early stress rather than misbehaviour or weakness. Developmental trauma can shape how a person experiences the world well into adulthood, but with understanding, stability, and supportive relationships, the nervous system can learn new patterns of safety and connection over time.

These responses reflect adaptation to early stress rather than misbehaviour or weakness. Developmental trauma can shape how a person experiences the world well into adulthood, but with understanding, stability, and supportive relationships, the nervous system can learn new patterns of safety and connection over time.

Secondary or Vicarious Trauma

Secondary trauma develops when a person is repeatedly exposed to other people’s distress or traumatic experiences, often through caring, supporting, or listening roles. This is common among carers, support workers, healthcare staff, emergency responders, and family members. Over time, hearing difficult stories, witnessing pain, or holding responsibility for others’ safety can begin to affect emotional wellbeing, leading to exhaustion, heightened anxiety, sleep difficulties, emotional withdrawal, or a changed sense of safety.

Medical Trauma

Medical trauma can develop through distressing or frightening healthcare experiences, particularly when a person feels powerless, unheard, or unsafe. It may follow a single event, such as an emergency procedure, or build up over repeated hospital stays, invasive treatments, or painful interventions. For some, trauma is linked not only to the medical event itself, but to how care was experienced — especially when communication was unclear or consent did not feel fully present.

- Experiences that may lead to medical trauma include:

- Emergency treatments or surgeries, especially when unexpected or life-threatening

- Invasive or painful procedures, particularly when repeated over time

- Loss of control or autonomy, including being restrained or sedated without clear understanding

- Feeling dismissed, rushed, or not listened to by medical staff

- Extended hospital stays, intensive care, or repeated admissions

- Medical procedures during childhood, when understanding and reassurance were limited

People affected by medical trauma may feel anxious around healthcare settings, avoid appointments, or experience physical stress responses when reminded of past treatment. These reactions reflect how frightening loss of control or safety can feel in medical environments, and why trauma-informed care, clear communication, and compassion matter deeply in healthcare settings.re, clear communication, and compassion matter deeply in healthcare settings.

The Impact of Trauma on Mental and Physical Health

Trauma affects mental and physical health in lasting ways, especially when traumatic experiences involve fear, loss, or lack of safety. Traumatic memories may return without warning, while prolonged exposure to stress can keep the body in a constant state of alert. Trauma linked to childhood abuse often shapes how the nervous system develops, with effects that can continue into adulthood. For trauma survivors, these responses reflect survival rather than weakness and often show up across daily life.

Common impacts include:

- Intrusive memories or flashbacks

- Anxiety, low mood, or emotional numbness

- Sleep difficulties, including nightmares or exhaustion

- Problems with concentration and memory

- Heightened stress responses, such as being easily startled

- Physical health concerns, including chronic pain, fatigue, headaches, or digestive issues

These effects highlight how trauma is carried not only in memory, but throughout the body and nervous system.

Can You Inherit Trauma?

Trauma is not inherited in the same way as physical traits, but research shows that its effects can be carried across generations. This happens through lived environments and biological stress responses shaped by prolonged or severe adversity. Studies involving families affected by war exposure, forced displacement, domestic violence, and chronic poverty have found altered stress regulation in both caregivers and their children.

Research has also explored intergenerational patterns among children of parents who experienced childhood abuse, long-term neglect, or repeated interpersonal trauma, showing higher sensitivity to stress and anxiety even when children were not directly exposed to the original events. These findings do not suggest trauma is fixed or unavoidable; they highlight how early environments, caregiving relationships, and emotional safety play a central role in shaping how stress responses are passed on or softened over time.

How Trauma-Informed Practices Support Healing

A trauma-informed approach starts by identifying trauma. It recognises that past experiences of harm, fear, or loss can shape behaviour, emotional responses, and engagement with care. Without this understanding, people are often misunderstood, and support can unintentionally reinforce distress.

Once trauma is identified, attention turns to the impact — including fears, triggers, coping responses, and protective behaviours. These are not treated as problems to fix, but as understandable responses to what someone has lived through. This understanding helps teams anticipate distress, reduce escalation, and avoid re-traumatisation.

Support is then shaped through person-centred planning, focused on what helps someone feel safe, understood, and able to be themselves. Care is delivered with clarity, consistency, and respect, reducing fear and power imbalance. At the centre of this approach is a clear shift in mindset:

“What has happened to you?”

rather than

“What is wrong with you?”

Trauma-informed practice supports healing by:

- Identifying trauma early, rather than reacting only to behaviour

- Understanding fears and triggers, and planning around them

- Creating safety, both emotional and physical

- Building trust, through consistency and transparency

- Offering choice and control, restoring a sense of autonomy

- Working collaboratively, alongside people and their support networks

By recognising trauma first and shaping support around lived experience, trauma-informed practice allows care to work with people – not against them – creating the conditions where healing can begin.

Trauma-Informed Care with Nurseline Community Services

Trauma-informed care at Nurseline Community Services recognises that experiences such as child abuse and long-term adversity can shape both mental and physical health, influencing how people respond to support. Care is designed with this understanding from the start, so people feel safe, understood, and supported rather than judged or overwhelmed.

Our trauma-informed approach focuses on:

- Identifying trauma, alongside fears, triggers, and coping responses

- Creating emotional and physical safety as the foundation for recovery

- Shaping person-centred support, built around trust and understanding

Support is delivered through a multidisciplinary team, including:

- Mental health professionals and Community Psychiatric Nurses (CPNs)

- Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) specialists

- Communication and multimedia specialists

Guided by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, safety and stability come first, allowing recovery and emotional wellbeing to develop at a sustainable pace.

For more information on how we can help you, contact us today or make a referral.