Out-of-area placements (OAPs) can have a serious effect on people’s well-being, often leading to psychological distress, disrupting family and social connections, and creating instability in care and living arrangements. Physical, psychological distress and anxiety are just a few of the negative impacts that out-of-area placements can have on children, young people and adults.

In 2025, England recorded 7,191 new inappropriate out-of-area placements – around 113 every week – with 381 involving children. The numbers paint a worrying picture, showing that more people, including children, are still being sent far from home for care.

Although efforts and initiatives have been made to end adult mental health out-of-area placements by March 2021, this goal has still not been achieved. Meanwhile, more and more people end up in mental health units, often for years and very far from home.

Learn more.

What Are Out-of-Area Placements?

An out-of-area placement (OAP) happens when someone with acute mental health needs is admitted to an inpatient unit outside their usual local service area. This distance makes it harder for care coordinators to visit regularly, which can affect continuity of care and discharge planning. Wherever possible, people should receive treatment close to home – in an environment that allows them to stay connected with family, carers, and friends, and remain in familiar surroundings.

Out-of-area placements within mental health services can sometimes be necessary – for example, when a person with acute mental health needs becomes unwell while away from home or requires safeguarding from situations such as domestic abuse or exploitation.

However, when these placements occur simply because there are no locally available beds or appropriate services, they are considered inappropriate and highlight gaps in local mental health provision.

Why Do Out-of-Area Placements Happen?

Out-of-area placements happen when a person is moved to a care setting far from home, often because there are no suitable local options available. In some cases, they’re necessary – for example, to ensure safety or to access specialist support.

But when they happen simply because there aren’t enough local beds, they can cause real difficulties. Being far away makes it harder for people to stay connected with family and support networks, and when there’s no clear clinical or safeguarding reason for the move, it can disrupt recovery and continuity of care.

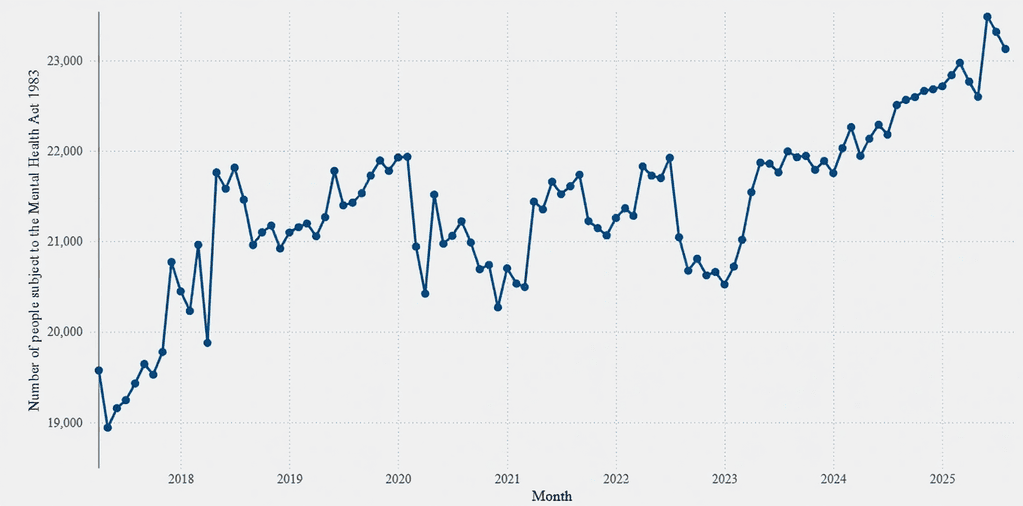

Out-of-area placements reflect wider strain across the entire mental health system, not just a shortage of acute mental health beds. Limited focus on early intervention, delays in discharge, growing demand on community services, insufficient crisis support, and the rising use of the Mental Health Act all contribute to bed pressures – which often result in greater dependence on out-of-area placements.

Source: mentalhealthwatch.rcpsych.ac.uk

Lack of Local Beds or Services

When there aren’t enough local beds or services for people with assessed acute mental health needs, out-of-area placements often become the last resort. This can happen when someone requires immediate inpatient support, but their local area lacks the capacity or resources to provide it. As a result, people are sent far from home to receive care, which can disrupt their recovery, separate them from family and support networks, and make coordination between teams more difficult.

According to NHS England (March 2024), around 89% of active out-of-area placements were classed as inappropriate, meaning people were sent away not because of clinical need, but due to a lack of local bed capacity or services.

Multiple and Long-Term Needs

Out-of-area placements often occur when a person has multiple or long-term support needs, particularly where mental health overlaps with developmental or neurodivergent conditions. This is common for people with autism, learning disabilities, ADHD, and related support needs, where care must consider sensory environments, communication differences, emotional regulation, physical health, and daily living skills.

When local services are not set up to provide this level of coordinated, ongoing support – or when specialist expertise is limited – the system can default to placements outside the person’s home area. In many cases, this happens not because the support doesn’t exist, but because it isn’t available locally, which can separate the person from family, familiarity, and community life.

Resource and Funding Challenges

Mental health services continue to face serious pressure from limited resources and funding. With not enough investment in local inpatient units, ongoing staff shortages, and stretched community and crisis teams, many people with acute mental health needs struggle to get the right support close to home. These gaps in local provision often lead to out-of-area placements, making care less consistent and recovery more difficult.

The Negative Impact

Being placed far from home for mental health care can be deeply distressing. Many people describe feeling lonely, cut off from their usual sources of comfort, and anxious about being in an unfamiliar environment.

Research by Health Services Safety Investigations Body (HSSIB) found that inappropriate OAPs are linked to increased lengths of stay, higher levels of anxiety and stress, cases of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) tied to transportation or unfamiliar settings, and even self-harm.

Disconnection From Family and Social Support

Being separated from family and friends during mental health treatment can feel deeply isolating. Staying connected to loved ones often provides comfort, reassurance, and a sense of normality – things that are crucial for recovery. When someone is placed far from home, visits become rare, conversations fade, and the distance can leave them feeling forgotten or alone. This loss of connection can make recovery slower and the transition back home more difficult.

Disruption to Continuity of Care

When someone is treated far from home, it becomes harder for care teams to work together and maintain consistency. Local professionals, who know the person’s history and needs best, often struggle to stay involved in their ongoing treatment and discharge planning. This lack of coordination can lead to gaps in communication, delays in follow-up support, and confusion about who is responsible for care once the person returns home – all of which can interrupt progress and make recovery more challenging.

For example, Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) states that when people are admitted outside their local area, there is a higher risk of delayed discharge because case-management is harder to deliver effectively over distance.

Negative Impact on Recovery and Rehabilitation

Being placed far from home can slow recovery and disrupt rehabilitation. The unfamiliar environment, distance from loved ones, and lack of consistent support can make it harder for people to engage in therapy or feel motivated to progress. Recovery is most effective when care is built around familiar routines, trusted relationships, and coordinated follow-up – all of which are harder to achieve when someone is treated out of area.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists reported that between December 2023 and November 2024, 319 children and young people were sent far from home to receive mental health treatment. Together, these placements amounted to 35,845 days spent away from their local communities, highlighting how many young people continue to face long separations from their families and familiar support networks.

Financial Strain on Families

When someone is placed far from home for mental health care, families often face huge practical and financial challenges. Travelling back and forth can mean spending money on petrol, train fares, or hotels – costs that quickly add up. Many parents and carers take time off work or rearrange their lives just to spend time with their loved one. What should be simple moments of connection and support often come with stress, exhaustion, and worry about how to manage it all.

Emotional Strain

Being treated far from home can feel deeply isolating. Someone might lie awake at night, longing for a familiar voice or a reassuring hug. At the same time, family members might sit in their living room, watching the clock, wondering how their loved one is coping miles away. That distance doesn’t just separate people-it shakes the foundations of support and care, leaving both the person and their carers weighed down by anxiety, helplessness and a persistent ache of disconnection.

Who is Most Affected by Out-of-Area Placements?

People most likely to be sent out of area are those whose needs can’t be met locally withint healthcare services at the point of crisis.

- Adults in acute mental health crisis, such as those experiencing recurrent psychosis, severe depression, or bipolar disorder, who require urgent inpatient admission when local beds are full or closed.

- Children and young people who need specialist inpatient care (CAMHS Tier 4) but face uneven bed availability, leading to placements far from home.

- People with autism or learning disabilities who need specialist inpatient support that isn’t available nearby, resulting in distant admissions.

- People detained under the Mental Health Act who are moved to available or specialist beds outside their home area.

- People from rural or underserved areas where community and crisis services are limited and inpatient capacity is low.

In short: out-of-area placements often affect people with complex or high-risk needs, when local healthcare services – including psychiatric intensive care units – lack the space, staff, or resources to provide the right support close to home.

The Systemic Challenges Behind the Issue

Out-of-area placements are not just the result of individual service gaps – they reflect deeper, systemic challenges across mental health care. Years of underfunding, uneven investment between regions, and a shortage of trained professionals have left many local services struggling to meet demand.

Community teams are overstretched, crisis responses are delayed, and inpatient units often operate at full capacity. These pressures create a cycle where people in urgent need are sent far from home, highlighting a system that is reactive rather than preventative.

Underfunded Local Mental Health Services

Local community mental health services are operating under growing pressure. Demand for support continues to rise, yet the resources needed to deliver timely, consistent care have not increased at the same pace. This leaves teams stretched thin and people waiting longer for the help they need.

- Referrals to community mental health services have risen by around one-third in recent years, while funding has increased by only about 10% in real terms.

- The proportion of the NHS budget allocated to mental health is expected to slightly decrease, despite continued increases in need.

- Cuts to wider local services, including early-help and social support, have removed important preventative support within the local community mental health system.

- Staff shortages across community teams lead to reduced capacity for follow-up, longer waiting lists, and less continuity of care.

In essence, demand is rising faster than investment, leaving local community mental health services struggling to provide timely and sustained support.

Workforce Shortages

Mental health services are facing growing workforce pressures, with demand rising much faster than staffing levels. Over the past few years, referrals to mental health services have increased by around 35–40%, yet the mental health nursing workforce has grown by only about 3%.

In some teams, staff vacancies account for nearly one in five roles, leaving those in post managing heavier caseloads and less time with each person. This makes it harder to build the steady, trusting relationships that support recovery, and leaves both staff and the people they care for feeling stretched and overwhelmed.

- Referrals to mental health services have increased by around 35–40% in recent years, while staffing levels have not kept pace.

- Mental health nursing numbers have grown by only about 3% over the same period.

- In some areas, around 1 in 5 mental health posts are vacant.

- High turnover means people may have to repeat their story to multiple professionals, making it harder to build trust.

- Staff working in stretched teams report heavier caseloads, shorter appointments, and reduced capacity for follow-up support.

What Needs to Be Done

Support needs to start early, with a clear focus on preventing crisis wherever possible. Personalised PBS plans and the PROACT-SCIPr-UK® approach should be used consistently to understand triggers, reduce distress, and promote stability day to day.

If a crisis does occur, there must be fast, community-based intervention – with community psychiatric nurses (CPNs) and crisis teams able to step in quickly, rather than hospital admission being the default option.

Alongside this, providers submit accurate information, agree on further treatment, and start effective discharge planning from the point of admission to ensure a safe and coordinated return home.

Nurseline Community Services Works on Reducing OAPs

Out-of-are placements can be prevented if the right help is available at the right time. Nurseline Community Services provides fast, specialist response for young people and adults experiencing mental health crises, combining clinical expertise with proactive, person-centred care to ensure continuity and stability during difficult moments.

Our approach includes:

- Proactive support using Positive Behaviour Support (PBS), PROACT-SCIPr-UK®, and multimedia tools that help understand behaviour and respond with insight rather than reaction.

- Trauma-informed practice that prioritises emotional safety, builds trust, and creates the space needed for recovery.

- Specialist clinical oversight from experienced mental health nurses and community psychiatric nurses, ensuring safe, consistent support at every stage.

- Collaboration with families and local professionals to stabilise situations early, reduce distress, and avoid unnecessary hospital admissions or out-of-area placements – keeping people connected to the lives and communities that matter.

We also provide temporary housing options to facilitate hospital discharges for people with autism, learning disability and/or mental health needs.

As independent providers, our goal is to support the national ambition to reduce hospital-based care where avoidable, while working closely with the local environment to strengthen community pathways and long-term wellbeing.

Reach out today to learn more about how we can support you in preventing hospital admission and out-of-area placements.