Physical Restraints in Mental Health Care

Physical restraint happens when one or more people use their own body to make someone do something against their will, or to prevent them from doing something they want to do. In the past, physical restraint was commonly used as a way to keep people safe – for example, to prevent them from self-harm or harm to others.

However, it’s now understood that restraint can often make situations worse. It can cause physical harm, lead to serious injuries, and have serious and lasting consequences on people’s physical and mental health.

While in some situations it may be necessary, it should always be the last resort. Recent practice shows that when the right support is provided at the right time, the need for any form of restraint – especially physical restraint can be avoided altogether.

Although it is meant to protect and manage situations, it still takes away a person’s freedom and affects their basic human rights. This raises important ethical questions about how much we respect people’s dignity and independence, especially for people with complex mental health needs, learning disabilities, and/or autism.

In most cases, the use of physical restraint has contributed to further worsening of person’s mental health, leading to the risk of developing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Use of Physical Restraints and Restrictive Practices

Physical restraint and other restrictive practices are sometimes used in care, health, or education settings when there is an immediate concern for safety. These interventions should never be routine or preventative, but applied only in exceptional circumstances, when all other de-escalation methods have been tried and failed.

They are intended to protect a person or others from serious harm, but because they restrict freedom and can cause distress, each use must be justified, proportionate, and time-limited.

Evidence shows that physical restraint use can lead to psychological harm, including the potential development of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This harm is particularly pronounced among people with pre-existing trauma or those receiving care in high-stress environments, such as intensive care units.

The latest NHS figures reveal 8,300 instances of restrictive interventions in just one month. These include physical, mechanical, and chemical restraints, along with situations where people were kept in isolation.

Worryingly, 2,680 of these interventions involved children.

Everyone deserves care that feels calm and respectful, especially in moments of distress. While some people have said that a careful physical intervention helped them feel protected, others have described restraint as unnecessary and emotionally painful.

Definition of PTSD

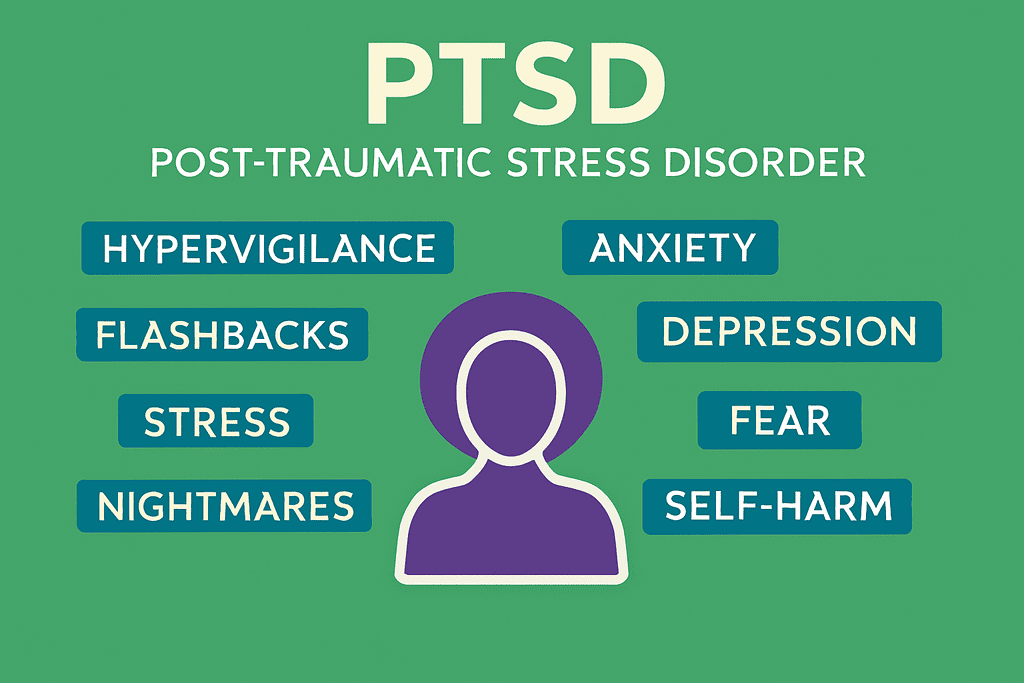

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) occurs after someone has lived through or witnessed a traumatic experience. Common symptoms include reliving the event through flashbacks or nightmares, avoiding reminders of it, feeling detached, tense, or easily irritated, and having trouble sleeping or focusing. These reactions can be so intense and long-lasting that they interfere with everyday life.

PTSD can develop after experiencing or witnessing deeply distressing events.

Common causes include:

- Serious accidents, assaults, natural disasters, or experiences of war and combat.

- The sudden or unexpected loss of a loved one, or other life-changing, distressing events.

- Severe illness or injury, including traumatic experiences during childbirth.

- Experiences of childhood or domestic abuse.

- Repeated exposure to traumatic events at work, such as in emergency or frontline services.

PTSD symptoms can appear weeks, months, or even years after the traumatic event. They usually fall into four main areas:

- Re-experiencing: Reliving the trauma through flashbacks, intrusive memories, or nightmares.

- Avoidance: Steering clear of people, places, or activities that bring back memories of the event.

- Negative thoughts and mood: Feelings of guilt, shame, or blame, and losing interest in things once enjoyed.

- Heightened arousal and reactivity: Being easily startled, feeling tense or on edge, irritability, angry outbursts, and difficulty sleeping or concentrating.

PTSD significantly impacts daily functioning, with affected people often struggling to maintain relationships, work, or engage in normal activities. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) classifies PTSD as a trauma-related disorder, requiring the presence of symptoms lasting for more than a month and causing significant distress or impairment.

PTSD Among People with Mental Health Challenges

People who are already living with mental health challenges can be more vulnerable to developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), especially when they face distressing or unsafe experiences. The combination of existing mental health needs and the effects of trauma can make recovery feel more difficult and overwhelming at times. This is why compassionate, joined-up, and trauma-informed support is so important – to help people feel safe, understood, and supported throughout their healing process.

People living with mental health challenges can be especially vulnerable when exposed to restrictive practices such as physical restraint. Being restrained during moments of crisis can be deeply distressing and may reopen old wounds or create new ones, making emotional recovery even harder. Research shows that PTSD often occurs alongside conditions like depression or substance use, highlighting how important it is to provide compassionate, trauma-informed care that understands and supports the whole person.

The Link Between Physical Restraints and PTSD

The use of physical restraints in healthcare, particularly in mental health and critical care settings, has been closely linked to the development of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Restraints, whether mechanical or chemical, are often used during acute crises to ensure safety. However, for the person being restrained, the experience can be profoundly distressing and even traumatic.

How Physical Restraint Can Lead to PTSD in People With Existing Mental Health Conditions

- Pre-existing emotional vulnerability

People who already live with anxiety, depression, psychosis, or other mental health conditions often experience heightened emotional sensitivity. Their ability to regulate fear, stress, and threat responses may already be strained due to ongoing psychological distress or past experiences. - The restraint event as a perceived threat

During physical restraint, even when intended to prevent harm, the person’s body and mind can interpret the act as a threat to safety. The sudden loss of control, physical force, and presence of multiple staff members can trigger an intense “fight, flight, or freeze” response – a survival mechanism linked to trauma. - Physiological response and memory imprint

In these moments, stress hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol surge. Heart rate and breathing accelerate, and the brain begins to encode the experience as a high-threat memory. This process can result in fragmented or sensory-based recollections that later resurface as flashbacks or nightmares. - Emotional meaning and interpretation

After the restraint, people may struggle to make sense of what happened – feeling humiliated, powerless, or betrayed by those meant to protect them. This emotional interpretation reinforces the traumatic impact, making it more likely that the memory becomes fixed and distressing rather than processed and integrated. - Re-experiencing and avoidance

Over time, reminders of the restraint – such as staff uniforms, certain rooms, or even the tone of voice used during support – can trigger involuntary flashbacks, panic, or emotional shutdown. People may start avoiding care settings, therapy, or relationships associated with the incident. - Progression to post-traumatic stress disorder

When these reactions persist for weeks or months, interfering with daily life, PTSD can develop. For someone who already has a mental health condition, this adds a second layer of difficulty – worsening anxiety, depression, or psychotic symptoms, and increasing the risk of isolation or disengagement from support. - Long-term consequences

Without timely understanding and psychological support, the trauma of restraint can shape how a person relates to care environments in the future – often resulting in fear, mistrust, or defensive behaviour that may increase the likelihood of further restraint, creating a damaging cycle.

Contributing Factors to PTSD from Physical Restraint Use

Several factors contribute to the development of PTSD among people subjected to physical restraints. One significant factor is the context in which restraints are applied. For instance, restraints used in high-stress environments like intensive care units (ICUs) or mental health facilities can exacerbate feelings of disorientation and fear. Prolonged restraint duration or inadequate communication during the intervention can intensify these negative emotions, increasing the risk of traumatic stress.

Another contributing factor is the lack of person-centred care during restraint use. When people feel misunderstood or unsupported, the experience of restraint can deepen feelings of isolation and mistrust. Moreover, restrictive practices are often employed in moments of crisis, amplifying the sense of chaos and unpredictability for the person being restrained. These experiences, particularly when compounded by previous trauma or adverse childhood experiences, can heighten the likelihood of developing PTSD. Addressing these factors requires a shift towards trauma-informed care that prioritises communication, empathy, and proactive interventions to prevent the need for physical restraints.

The Impact of Physical Restraints on People

Being physically restrained can be one of the most frightening experiences a person goes through. It can leave behind feelings of fear, humiliation, and worthlessness, often long after the moment has passed. Many people describe losing trust in those around them – and in the care services meant to help them feel safe. For some, the experience can also feel like a violation of their basic human rights, taking away their sense of dignity, choice, and control.

Short-term Impact

In the immediate aftermath of being restrained, people often experience heightened emotional distress, including fear, anger, and confusion. The loss of autonomy and the invasive nature of restraints can exacerbate feelings of helplessness and vulnerability, particularly in those with pre-existing trauma or mental health challenges. Physical discomfort, bruising, and injuries may also occur, adding to the distress. Additionally, restraints can disrupt therapeutic relationships, leading to mistrust between the person and their care team. In critical care settings, restraint use during mechanical ventilation may contribute to delirium and increased agitation, complicating recovery.

Long-term Consequences

The long-term effects of physical restraint use can be deeply damaging, particularly when it leads to the development of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). People who have been restrained may experience recurring flashbacks, nightmares, and heightened anxiety, often associating healthcare environments with trauma. This can deter them from seeking future care, resulting in untreated conditions and deteriorating health. Furthermore, the psychological harm from restraints can impact relationships, employment, and overall quality of life, creating additional barriers to recovery. These long-term consequences underscore the urgent need to reduce reliance on physical restraints and adopt trauma-informed, person-centred practices that prioritise dignity and psychological safety.

Strategies for Mitigating the Impact of Physical Restraints

To address the negative effects of physical restraints, healthcare systems must adopt strategies that focus on prevention, early intervention, and alternative practices. Mitigating the impact of restraints requires a shift towards person-centred, trauma-informed care that prioritises safety, dignity, and well-being. Implementing positive approaches and ensuring comprehensive training for healthcare providers can significantly reduce the need for restraints, fostering a more supportive and compassionate care environment.

Alternative Positive Approaches

Instead of relying on restrictive practices, positive approaches focus on understanding, prevention, and meaningful support. They aim to build trust, reduce distress, and create safer, more empowering environments for everyone involved.

- Proactive Support

Rather than waiting for a crisis to happen, proactive support anticipates needs early on. It involves recognising early signs of distress, adapting environments, and providing reassurance before behaviour escalates. This approach helps people feel safe and understood, reducing the likelihood of crisis situations altogether.

- Strength-based Approach

A strengths-based approach focuses on what a person can do, rather than what they can’t. It recognises people’s skills, interests, and potential, and uses these strengths as the foundation for support and recovery. By celebrating abilities, it builds confidence and encourages positive self-identity.

- Positive Behaviour Support (PBS)

PBS is a framework that looks beyond the behaviour itself to understand its purpose or meaning. It combines behavioural science with person-centred values to identify triggers and teach alternative ways of communicating needs. The goal is to improve quality of life, not just to reduce challenging behaviour.

- PROACT-SCIPr-UK®

This is a structured, values-based approach to supporting people with complex needs and behaviours that challenge. It promotes proactive planning, understanding the reasons behind distress, and using respectful communication to prevent escalation. Physical intervention is only used as a last resort, with an emphasis on care, safety, and dignity.

- Positive Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement means recognising and rewarding desirable behaviour to encourage it to happen again. This could be through praise, meaningful activities, or opportunities for choice and independence. It focuses on motivation, not punishment, and helps create positive relationships built on trust and encouragement.

• Individualised Support

Every person’s experiences, needs, and preferences are different. Individualised support means adapting care to fit the person – not the other way around. It considers communication styles, triggers, routines, and aspirations to ensure support feels respectful and responsive.

- Personalised Support

Personalised support goes a step further by involving the person directly in planning their care. It ensures their voice, choices, and goals guide every decision. This collaborative process builds ownership, confidence, and a sense of control over one’s own life.

Appropriate Training for Care Providers

Comprehensive training for healthcare providers is essential in reducing reliance on physical restraints and improving outcomes for people receiving care. Training should focus on trauma-informed care principles, equipping staff with the skills to recognise signs of distress and respond with empathy and professionalism. Role-playing scenarios and workshops on conflict resolution, de-escalation, and therapeutic communication can empower providers to manage crises effectively without resorting to restrictive practices.

Training programs are regularly reviewed and updated to ensure staff remain informed about the latest evidence-based practices and ethical considerations. Additionally, fostering a culture of accountability and reflective practice encourages teams to continuously assess the necessity and impact of their interventions, promoting safer and more compassionate care. By prioritising education and awareness, healthcare systems can take significant steps toward reducing the impact of physical restraints and enhancing overall care quality.

Importance of Reducing Restrictive Practices in Health and Social Care

Reducing restrictive health and social care practices is essential for both the wellbeing of people receiving support and the sustainability of health and social care systems. When restrictive measures such as restraint, seclusion, or enforced control are used, they can create a deep and lasting chain of negative effects. On a personal level, people may experience fear, trauma, and loss of trust, which can delay emotional and psychological recovery. Prolonged distress often leads to longer hospital stays, repeated crises, and increased dependency on services.

At a systemic level, the continued use of restrictive practices places additional strain on hospitals, care teams, and resources, leading to staff burnout, higher costs, and reduced capacity to provide proactive care. Over time, this cycle perpetuates reactive rather than preventative responses, further embedding inefficiencies within the system. Reducing restrictive practices not only protects people’s dignity and human rights but also supports faster recovery, smoother transitions back to the community, and a more compassionate and effective model of care.

How Care Providers Can Minimise Use of Restraints

Reducing restraint is central to safer and more compassionate mental health care. In 2025, NHS data showed 870 people with learning disabilities and/or autism were restrained at least once in a single month, and 1,123 incidents were recorded among children and young people in secure settings. These figures show how much more can be done to prevent distress before it reaches crisis point.

Real progress happens when services move from reaction to prevention. The NHS Restrictive Practice Reduction Programme reported a 15% fall in restraint and seclusion incidents across 38 pilot wards that focused on early intervention, communication, and consistent staff training. Approaches like Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) and PROACT-SCIPr-UK® help staff understand the reasons behind behaviour and respond calmly, reducing the need for control.

By reviewing every incident, strengthening leadership, and promoting personalised alternatives that build trust, care providers can create environments where restraint becomes the rare exception. The goal is simple but transformative – care where safety is achieved through understanding, and dignity is never compromised.

Nurseline Community Services is Dedicated to Reducing Restrictive Practices

Nurseline Community Services is committed to creating care environments that prioritise dignity, safety, and empowerment. We adopt trauma-informed, person-centred approaches that minimise the need for restrictive practices such as physical restraints or seclusion. By focusing on proactive strategies like therapeutic communication, de-escalation techniques, and personalised care planning, we aim to address challenges before they escalate into crises. Our multidisciplinary teams work closely with people and their families to identify triggers, build trust, and create tailored support plans that align with each person’s unique needs and preferences.

Our dedication extends to continuous staff training, ensuring our teams have the skills and knowledge to provide compassionate, effective care. We believe in fostering collaboration and using evidence-based practices to reduce restrictive interventions, promoting better outcomes and holistic recovery. Together, we can redefine care and create supportive environments where everyone feels valued.

Reach out to learn more about how our services can make a difference in person-centred, progressive care.